Exerpt from Smithsonian article, Inside the Story of America’s 19th-Century Opiate Addiction, by Erick Trickey

1. The man was bleeding, wounded in a bar fight, half-conscious. Charles Schuppert, a New Orleans surgeon, was summoned to help. It was the late 1870s, and Schuppert, like thousands of American doctors of his era, turned to the most effective drug in his kit. “I gave him an injection of morphine subcutaneously of ½ grain,” Schuppert wrote in his casebook. “This acted like a charm, as he came to in a minute from the stupor he was in and rested very easily.”

2. Physicians like Schuppert used morphine as a new-fangled wonder drug. Injected with a hypodermic syringe, the medication relieved pain, asthma, headaches, alcoholics’ delirium tremens, gastrointestinal diseases and menstrual cramps. “Doctors were really impressed by the speedy results they got,” says David T. Courtwright, author of Dark Paradise: A History of Opiate Addiction in America. “It’s almost as if someone had handed them a magic wan

3. By 1895, morphine and opium powders, like OxyContin and other prescription opioids today, had led to an addiction epidemic that affected roughly 1 in 200 Americans. Before 1900, the typical opiate addict in America was an upper-class or middle-class white woman. Today, doctors are re-learning lessons their predecessors learned more than a lifetime ago.

4. Opium’s history in the United States is as old as the nation itself. During the American Revolution, the Continental and British armies used opium to treat sick and wounded soldiers. Benjamin Franklin took opium late in life to cope with severe pain from a bladder stone. A doctor gave laudanum, a tincture of opium mixed with alcohol, to Alexander Hamilton after his fatal duel with Aaron Burr.

5. The Civil War helped set off America’s opiate epidemic. The Union Army alone issued nearly 10 million opium pills to its soldiers, plus 2.8 million ounces of opium powders and tinctures. An unknown number of soldiers returned home addicted, or with war wounds that opium relieved. “Even if a disabled soldier survived the war without becoming addicted, there was a good chance he would later meet up with a hypodermic-wielding physician,” Courtright wrote. The hypodermic syringe, introduced to the United States in 1856 and widely used to deliver morphine by the 1870s, played an even greater role, argued Courtwright in Dark Paradise. “Though it could cure little, it could relieve anything,” he wrote. “Doctors and patients alike were tempted to overuse.”

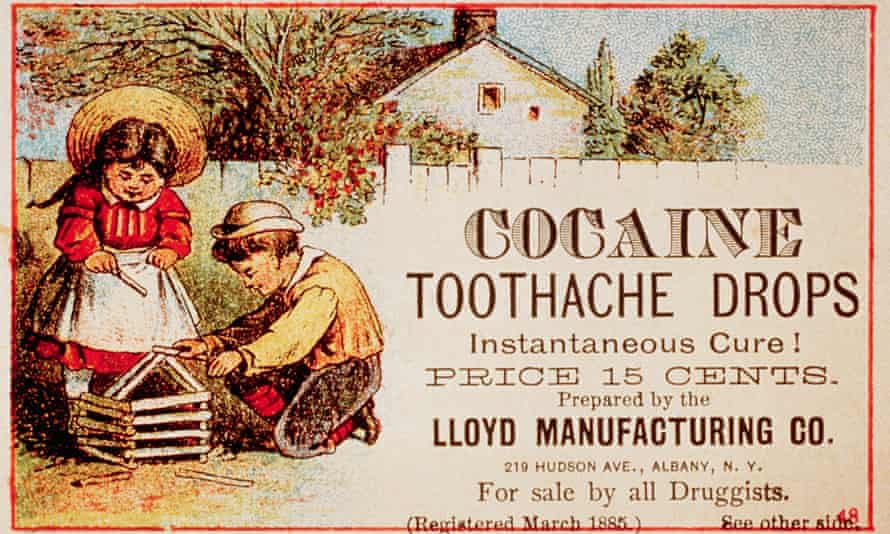

6.Opiates made up 15 percent of all prescriptions dispensed in Boston in 1888, according to a survey of the city’s drug stores. “In 1890, opiates were sold in an unregulated medical marketplace,” wrote Caroline Jean Acker in her 2002 book, Creating the American Junkie: Addiction Research in the Classic Era of Narcotic Control. “Physicians prescribed them for a wide range of indications, and pharmacists sold them to individuals medicating themselves for physical and mental discomforts.”

7. Male doctors turned to morphine to relieve many female patients’ menstrual cramps, “diseases of a nervous character,” and even morning sickness. Overuse led to addiction. By the late 1800s, women made up more than 60 percent of opium addicts. “Uterine and ovarian complications cause more ladies to fall into the [opium] habit, than all other diseases combined,” wrote Dr. Frederick Heman Hubbard in his 1881 book, The Opium Habit and Alcoholism.

8. Throughout the 1870s and 1880s, medical journals filled with warnings about the danger of morphine addiction. But many doctors were slow to heed them, because of inadequate medical education and a shortage of other treatments. “In the 19th century, when a physician decided to recommend or prescribe an opiate for a patient, the physician did not have a lot of alternatives,” said Courtwright in a recent interview. Financial pressures mattered too: demand for morphine from well-off patients, competition from other doctors and pharmacies willing to supply narcotics.

9. Only around 1895, at the peak of the epidemic, did doctors begin to slow and reverse the overuse of opiates. Advances in medicine and public health played a role: acceptance of the germ theory of disease, vaccines, x-rays, and the debut of new pain relievers, such as aspirin in 1899. Better sanitation meant fewer patients contracting dysentery or other gastrointestinal diseases, then turning to opiates for their constipating and pain-relieving effects.

10. Educating doctors was key to fighting the epidemic. Medical instructors and textbooks from the 1890s regularly delivered strong warnings against overusing opium. “By the late 19th century, [if] you pick up a medical journal about morphine addiction,” says Courtwright, “you’ll very commonly encounter a sentence like this: ‘Doctors who resort too quickly to the needle are lazy, they’re incompetent, they’re poorly trained, they’re behind the times.’” New regulations also helped: state laws passed between 1895 and 1915 restricted the sale of opiates to patients with a valid prescription, ending their availability as over-the-counter drugs.

Book Club Questions: OPIUM AND ABSINTHE

1. How does Tillie’s relationship to opiates change as the story moves along? Do you think this was a realistic portrayal of addiction, even though it was in 1899?

2. Tillie changes throughout the story. Where do you think was the most significant turning point for her in her character development?

3. There are moments when her mother and grandmother seemed bent on controlling Tillie in the harshest ways possible. Did you ever feel sympathy for them?

4. At one point, her grandmother says, “No woman lives a life unscathed. It’s what makes us strong. We are broken and mended, remade every time. We must, or it destroys us.” To what do you think she is referring? Does this quote mean something in your own life you are willing to share with the group?

5. Another time, her grandmother says, “Forgetting is an act of survival.” Do you agree?

6. Tillie is wealthy, pretty, and smart. And yet, she faces restrictions throughout the story which she must battle to solve the mystery. In what ways did her privilege still give her passes to do things that others might not at the time?

7. There is a strong sister story in this book, despite Lucy being deceased. How does Lucy change as the story goes on, though her character is technically static and unchanging?

8. Which character was the most repulsive, and why? Make a case.

9. If you could hear this book from another character’s point of view, who would it be?

10. Were there any parts of this book that surprised you?

Returns by Lydia Kang,

Comments

Post a Comment