- Is Pablo opposed to blowing the bridge because he is a coward, as Pilar says, or is Pablo, himself, correct when he says he "has a tactical sense"? Why does Jordan agree with Pablo's reference to "the seriousness of this" (p. 54)? Is Agustín correct when he calls Pablo "very smart" (p. 94)?

- Was the communist effort to eliminate God successful? What does Anselmo's view of killing suggest about the limitations of dogma? What does he mean when he says of the bridge sentries, "It is only orders that come between us" (pp. 192-193)? What is implied when Anselmo says soldiers should atone and cleanse themselves after the war?

- The book begins and ends with the same image of Robert Jordan lying on the forest floor. Some argue that this establishes an underlying circularity in the book. In what ways might the book be circular?

- It's become increasingly popular for feminist scholars to hate on Hemingway for creating shallow, formulaic, and stereotypical women in his books who either exist to serve men or are themselves basically just men. Do Maria and Pilar fit this characterization? Why might they, and why might they not?

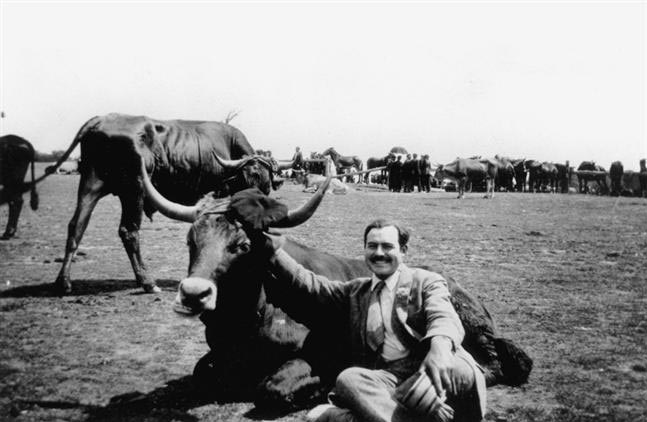

- To what extent do you think Robert Jordan is a vehicle for expressing Hemingway's own thoughts, and to what extent is Hemingway distanced from him? What in the text would lead you to go in one direction or the other?

- Why does the narrator use Robert Jordan’s whole name throughout the book? Why does he use other repetitive terms like “rope-soled shoes”? Can you name anything else used repetitively like that? Did you ever get tired of hearing them? What do the repetitive names and terms do for the narrative? If we know that all the characters are speaking Spanish, why are Spanish phrases used all the time? What effect does that have?

- In Chapter 23, pg. 296-7, Agustin is talking about his desire to kill the cavalry, saying that “‘the necessity was on me as it is on a mare in heat.’” Does this mean that Agustin likes to kill? Does this eagerness to kill make Agustin a bad person? Does Robert Jordan judge anyone for their views on killing? Why would he make the comparison of killing to sex? Does anything else in this book make that comparison? How might sex and killing be similar for someone in a war?

- From the beginning, Robert Jordan seems to understand that this is likely a deadly job he must do: “he resented Golz’s orders, and necessity for them. He resented them for what they could do to him and for what they could do to this old man” (pg. 46, Chapter 3). Since both Jordan and Anselmo die at the end, he clearly had the right suspicion that the mission could be suicidal. How did that affect Robert Jordan? Did that change the way he lived in the next four days? If Pilar actually can read his palm or smell death on him, then why does she encourage Maria to love Robert?

- Pilar’s story of Pablo killing the fascists in their hometown seems as much farce as tragedy. What’s important about this story? What does is reveal about the war? Does it tell us anything about Pablo or Pilar? What does Robert Jordan get from the story?

- On page 144, Chapter 11, Robert Jordan sees Maria as an impossible dream, and even wonders if he’s made her up. What does he like so much about Maria? Is Maria the “perfect” woman? Does it seem misogynistic for him to love a woman who’s so demure? How does Maria manage to get her way?

- On pg. 161, Chapter 12, Pilar seems to bully Maria after leaving Maria and Robert Jordan alone in the heather. She claims that she’s “very jealous,” but Maria says to Pilar that “‘It was thee explained to me there was nothing like that between us.’” What is not being said in the conversation? What is Pilar jealous of?

- Pilar gives the story of her previous boyfriend, the matador Finito. What does the story of the scared and dying matador add to the story of the war? Why did he fight if he was deathly afraid of bulls before entering the ring? Why did he continue to fight when he became injured? Is there any similarities between the matador and Padro?

- The narration switches often from 1st person to 2nd person to 3rd person point-of-view. Please find an example paragraph of each and read them aloud. What do each of these different viewpoints do for the story? Why does the narration switch up so often?

- Does the epigraph, an excerpt from John Donne's Devotions XVII, convey the theme of For Whom the Bell Tolls? What is that theme? What scenes in the novel develop the sentiment of the epigraph? What is the narrator telling us when he says that Robert Jordan, lying on the forest floor waiting for death, is "completely integrated" (p. 471)?

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

1. Thoughts form the Bath Blokes Book Club: NOTES ON BOOKS READ BY THE BBBC. HONEST, OPINIONATED, QUITE OFTEN ILL-INFORMED, WE ARE EIGHT BLOKES WHO LIKE READING. WE'RE MOSTLY (NOT ALL) IN OUR 50S OR 60S, MOSTLY (NOT ALL) MARRIED - THOUGH WE'VE ALL GOT KIDS. WE READ TO TAKE OUR MINDS OFF THE PROSPECT OF ENDLESS PAID DRUDGERY, OR TO FILL THE HOURS THAT EITHER RETIREMENT OR LACK OF WORK HAS PUT IN OUR HANDS.

For Whom The Bell Tolls – Ernest Hemingway

Late May 2009

2. A small but elegant group (in the words of Steve) at the Star last Thursday - Steve, Ras, Neil and myself. Plus, emailed comments received in advance from Chris W.

Despite the small number of people - and indeed a remarkable degree of agreement amongst those present - the debate about 'For Whom The Bell Tolls' (I will henceforth adopt Mark Th's abbreviation of 'Frome') was full, lively and varied. Despite CE's departing comment that Frome drove him over the edge, we all rather liked it. Not only was the writing style appreciated (with one caveat - see below), we collectively found it educational, thought provoking and almost moving in some ways.

3. One of the best things about the book was the way in which it prompted us into debates at the meeting about issues connected to both the story and its context. As Neil said at the end, one of the good things about the book club is the way in which the discussion helps us to see and/or recall things in books that we perhaps hadn't been fully conscious of at the time of reading it.

So, brief summary of some of the main areas of discussion:

All very impressed with the writing style and in particular his ability to paint a picture of a place, event or person.

4. The one significant disagreement around writing style was around his 'Thou', 'Thee' and 'I obscenity in the milk of your mother'. Ras, Neil and I found it very annoying. Steve and Chris didn't.

Unanimous agreement that the description of the lynching of the Fascists in the village square was incredibly powerful and well written. Using the style of monologue through Pilar worked well and drew us all into the story - to the extent of each thinking how they would have behaved in that situation. An ensuing discussion was around the nature of peer group pressure to behave in ways that might be alien to individual characteristics but perhaps bring out deeper (and darker) elements of human nature.

5. The book was set in a time and political situation of which we all had a vague outline knowledge, but didn't really know the detail. It therefore had an educational component. Resultant discussions around this element included (i) the extent to which it was written in a politically 'neutral' manner. On one hand it did appear written in a fairly balanced way, but is it really possible to write without personal political prejudices coming into play and Hemingway clearly must have had those given him living through that period in the area.,

6.(ii) the extent to which the scars of that period are still around in Spanish society today. Given that people are still alive who lived through it, there must surely be some residual animosity around the place, and it is, after all, only around 20 years since Franco and his repressive regime were ruling the country.

7. This led into numerous other discussions covering topics such as Gibraltar, why Spain has returned to a monarchy and the extent to which his description of the role of the Russians was influenced by wider political events on the early 1940's and how it made sense to describe their involvement in Spain. Finally, the interesting question of how and why fascist Spain stayed theoretically 'neutral' in the 2nd world war and how, had they not, the whole course of the war and subsequent history would have been different e.g. the Allies would almost certainly have lost control of the Mediterranean

8. The extent to which some of the writing style might have been innovative for its time e.g. the reflective wondering out-loud by Robert Jordan about the risk of imminent death, elements of his life etc. It didn't really feel like a book that was nearly 70 years old (apart from the thee, thou and obscenities).

The sex scenes were particularly appreciated - not because of the sex (as it wasn't really there in terms of the words) but because the writing style of those paragraphs eloquently described the emotions without being at all graphic.

9. Some suggestion that Hemingway had actually written very sympathetically about the female characters (surprising for a man with a reputation as a misogynist) i.e. Maria showing strength after the rape, Pilar being the strongest character in the book. I was a bit less convinced about this, thinking that Maria was being portrayed as an accepting, obedient subservient female whilst Pilar was enabled to be a strong person by having had most of her feminine characteristics stripped from her.

Robert Jordan's death scene - generally felt to be well written - which in turn led to a conversation about how we might react when faced with death - deep stuff eh?

Further Reading if you want more regarding Whom the Bell Tolls:

NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER • The bestselling author of The Paris Wife brings to life the story of Martha Gellhorn—a fiercely independent, ambitious woman ahead of her time, who would become one of the greatest war correspondents of the twentieth century.

NAMED ONE OF THE BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR BY The Washington Post • New York Public Library • Bloomberg • Real Simple

In 1937, twenty-eight-year-old Martha Gellhorn travels alone to Madrid to report on the atrocities of the Spanish Civil War and becomes drawn to the stories of ordinary people caught in the devastating conflict. It’s her chance to prove herself a worthy journalist in a field dominated by men. There she also finds herself unexpectedly—and unwillingly—falling in love with Ernest Hemingway, a man on his way to becoming a legend.

On the eve of World War II, and set against the turbulent backdrops of Madrid and Cuba, Martha and Ernest’s relationship and careers ignite. But when Ernest publishes the biggest literary success of his career, For Whom the Bell Tolls, they are no longer equals, and Martha must forge a path as her own woman and writer.

Heralded by Ann Patchett as “the new star of historical fiction,” Paula McLain brings Gellhorn’s story richly to life and captures her as a heroine for the ages: a woman who will risk absolutely everything to find her own voice.

The extraordinary untold story of Ernest Hemingway's dangerous secret life in espionage

A NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER • A finalist for the William E. Colby Military Writers' Award

"CAPTIVATING" (Missourian) • "IMPORTANT" (Wall Street Journal) • "FASCINATING" (New York Review of Books)

A riveting international cloak-and-dagger epic ranging from the Spanish Civil War to the liberation of Western Europe, wartime China, the Red Scare of Cold War America, and the Cuban Revolution, Writer, Sailor, Soldier, Spy reveals for the first time Ernest Hemingway’s secret adventures in espionage and intelligence during the 1930s and 1940s (including his role as a Soviet agent codenamed "Argo"), a hidden chapter that fueled both his art and his undoing.

While he was the historian at the esteemed CIA Museum, Nicholas Reynolds, a longtime American intelligence officer, former U.S. Marine colonel, and Oxford-trained historian, began to uncover clues suggesting Nobel Prize-winning novelist Ernest Hemingway was deeply involved in mid-twentieth-century spycraft -- a mysterious and shocking relationship that was far more complex, sustained, and fraught with risks than has ever been previously supposed. Now Reynolds's meticulously researched and captivating narrative "looks among the shadows and finds a Hemingway not seen before" (London Review of Books), revealing for the first time the whole story of this hidden side of Hemingway's life: his troubling recruitment by Soviet spies to work with the NKVD, the forerunner to the KGB, followed in short order by a complex set of secret relationships with American agencies.

Starting with Hemingway's sympathy to antifascist forces during the 1930s, Reynolds illuminates Hemingway's immersion in the life-and-death world of the revolutionary left, from his passionate commitment to the Spanish Republic; his successful pursuit by Soviet NKVD agents, who valued Hemingway's influence, access, and mobility; his wartime meeting in East Asia with communist leader Chou En-Lai, the future premier of the People's Republic of China; and finally to his undercover involvement with Cuban rebels in the late 1950s and his sympathy for Fidel Castro. Reynolds equally explores Hemingway's participation in various roles as an agent for the United States government, including hunting Nazi submarines with ONI-supplied munitions in the Caribbean on his boat, Pilar; his command of an informant ring in Cuba called the "Crook Factory" that reported to the American embassy in Havana; and his on-the-ground role in Europe, where he helped OSS gain key tactical intelligence for the liberation of Paris and fought alongside the U.S. infantry in the bloody endgame of World War II.

As he examines the links between Hemingway's work as an operative and as an author, Reynolds reveals how Hemingway's secret adventures influenced his literary output and contributed to the writer's block and mental decline (including paranoia) that plagued him during the postwar years -- a period marked by the Red Scare and McCarthy hearings. Reynolds also illuminates how those same experiences played a role in some of Hemingway's greatest works, including For Whom the Bell Tolls and The Old Man and the Sea, while also adding to the burden that he carried at the end of his life and perhaps contributing to his suicide.

A literary biography with the soul of an espionage thriller, Writer, Sailor, Soldier, Spy is an essential contribution to our understanding of the life, work, and fate of one of America's most legendary authors

Comments

Post a Comment